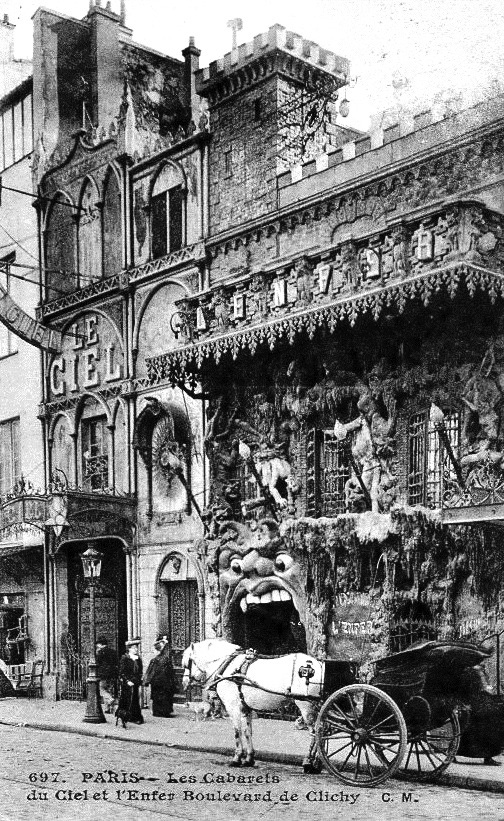

While meandering through the vastness of cyberspace, I found myself immersed in old analogue photographs and archival material of the intriguing Parisian phenomenon known as the “Cabarets of the Beyond”: the Cabaret De L’Enfer (the Cabaret of Hell), the Cabaret du Ciel (of Heaven), and the Cabaret du Néant (of Nothingness). As night deepened in the heart of the glittering capital’s Montmartre neighbourhood in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, flâneurs could escape the mundane and seek refuge in the enrapturing and otherworldly embraces of both Heaven and Hell during the same night, as they were situated at the same address. Diminishing the veil between worlds, the Dantesque cabarets represented a stirring source of entertainment and inspiration for guests from different walks of life, as well as a fitting backdrop for avant-garde artists and bohemian intellectuals in particular.

The Cabaret du Ciel greeted wandering – damned and divine – souls with blue lights and ethereal archways, whilst the neighbouring entrance of the Cabaret de l’Enfer allowed them to be devoured by the flames of hell in the grotesque jaws of the Leviathan. A little bit further away, one could find the arguably more unsettling Cabaret of Nothingness, which was a celebration of the essence and process of death, embodying a more worldly and macabre approach to the concept. The grim exterior of the latter was black and unadorned, except for the eerie green lanterns casting an otherworldly, cadaverous glow upon the unwary faces of the guests.

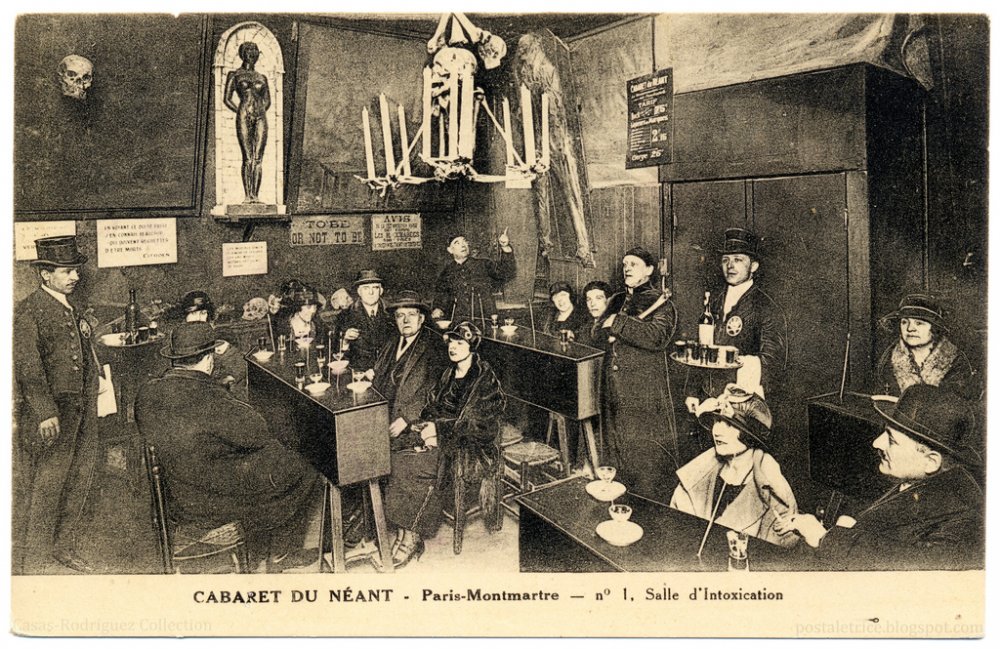

Inside the Cabaret du Néant, people were led by a monk-like figure through a dark hall towards a sinister café. In the Intoxication Hall, a chandelier crafted entirely from human bones cast a flickering eerie light upon the setting below, which consisted of coffin-shaped tables adorned with deathly flowers, dismembered arms with candles in their fingers, waiters dressed as undertakers who addressed the patrons as “corpses”, and disquieting depictions of battles and executions seemingly resurrected by the flickering lights. The unearthly, foreboding ambiance of the stage was merely a prelude to the performance that was about to unfold. Bells tolled. A funeral march entranced the audience. A sombre young man dressed in black held a transfixing discourse on the anguish and misery of death, pointing at the macabre imagery on the walls. The visuals would suddenly glow and become imbued with life as ghastly figures started emerging from the frames. Portrayals of fighting, living men turned into haunting images of skeletons writhing in a deathly embrace, as if they were fighting a never-ending battle.

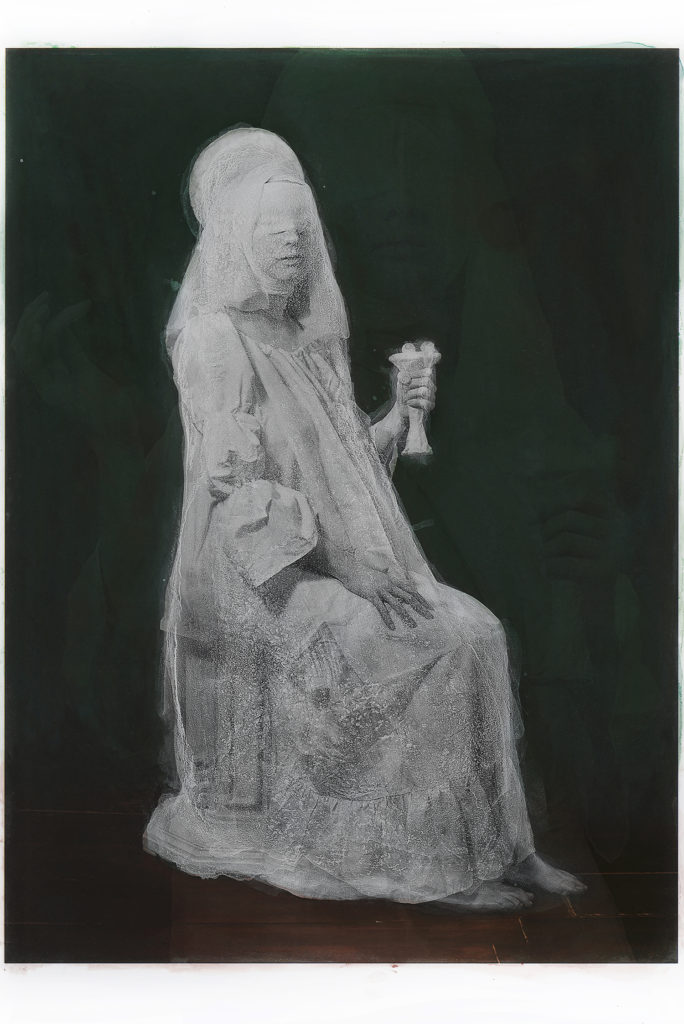

With the help of mirrors, lights, and hidden rooms, the disoriented audience could witness the gradual decomposition of bodies. In a smaller room, the “Room of Disintegration”, a beautiful, pale, uncannily alive young woman in a white veil was enclosed in a coffin. Here is an excerpt from William Chambers Morris’ “Bohemian Paris of Today” (1899), which describes the experience through his eyes:

“Soon it was evident that she was very much alive, for she smiled and looked at us saucily. But that was not for long… Her face slowly became white and rigid; her eyes sank; her lips tightened across her teeth; her cheeks took on the hollowness of death—she was dead. But it did not end with that. From white the face slowly grew livid… then purplish black… the eyes visibly shrank away into their greenish-yellow sockets… Slowly the hair fell away… The nose melted away into a purple putrid spot. The whole face became a semi-liquid mass of corruption. Presently all this had disappeared, and a gleaming skull shown where so recently had been the handsome face of a woman; naked teeth grinned inanely and savagely where rose lips had so recently smiled.”

Compared to the other two cabarets, the Cabaret du Néant was notably different mood-wise and far less light-hearted. Not everyone appreciated the cabaret’s earthly, corporeal, macabre approach to death. Jules Claretie noted, “a sinister irony was expressed, not with angels and devils, but with people, mortals, death”. The French journalist also perceived the Cabaret du Néant created by illusionist M. Dorville to be ghastly and mean-spirited compared to Antonin Alexander’s Cabaret of Hell.

Renault and Château expressed their critical point of view in their book, “Montmartre”, stating: “if the Ciel and Enfer of the lovable M. Antonin merit a visit, this is not true of the Néant, which is frequented by hysterical and neurotic persons”.

Despite the scarcity of visual archive material featuring the cabarets, judging by literary accounts providing first-hand snap shots of nightlife in Paris, it’s hardly surprising that the Cabaret du Néant was found to be more disturbing. It seems to have embodied a visceral approach with painful reminders of mortality whilst focusing on the actual process and ritual of death in a way that made people face a primal fear. Moreover, some aspects of it created an uncanny experience, which would automatically involve the elements of emotional shock and repulsion. Besides the uncanny acts from the room of disintegration, there were other elements that were subtly frightening, nihilistic, and potentially psychologically scarring for some, as the cabaret of the void focused on conveying the emptiness of existence in a surreal way that had the effects of psychological horror.

Meanwhile, despite the profane theme it depicted, the unholy Cabaret de l’Enfer was less anchored in secular, materialistic reality and more rooted in the intangible and unearthly, which might have been one of the characteristics that made it less disconcerting. However, it was also not exactly for the faint of heart. After entering the infernal mouth-portal, past the embers that were stirred by a frenzied scarlet demon in the depths of hell, one would be welcomed by meticulous hell-themed decorations, ghoulish images of demons, dioramas of sinners being punished, and staff dressed in devil costumes. A cauldron was hanging over a hellfire, partially enveloping several devil musicians eerily playing “Faust” on stringed instruments, being prodded with red-hot irons for every discordant note.

After having their orders taken by a devilish being whose discourse was characterised by consistently twisted, macabre, yet playful words and arcane incantations, the damned souls who ventured in this hellish place would get to drink liquids that were supposed to ease their upcoming suffering, from glasses with an eerie, phosphorescent, unearthly glow. Meanwhile, the place pulsed with dark energy. There was a palpable, ominous sense of unholiness in the air. Volcanos were blasting and streams of molten precious metals were trickling from the crevices of the underground rock structure of the walls.

Imagine being there, surrounded by figures and symbols of the macabre, witnessing nightmarish scenes, soaking up the atmosphere, sipping glowy liquids, and catching sight of André Breton in one of his meetings with the Surrealists. The Cabaret de l’Enfer served as a gathering place for the Surrealists in the 1920s – and a popular one, at that. Unsurprisingly, the Surrealists were drawn to the cabaret’s macabre aesthetic, due to their fascination with the unconscious mind and penchant for the bizarre and the subversive. Breton’s studio was located on the fourth floor above the cabaret, which is where he and Robert Desnos arranged his well-known surrealism sessions.

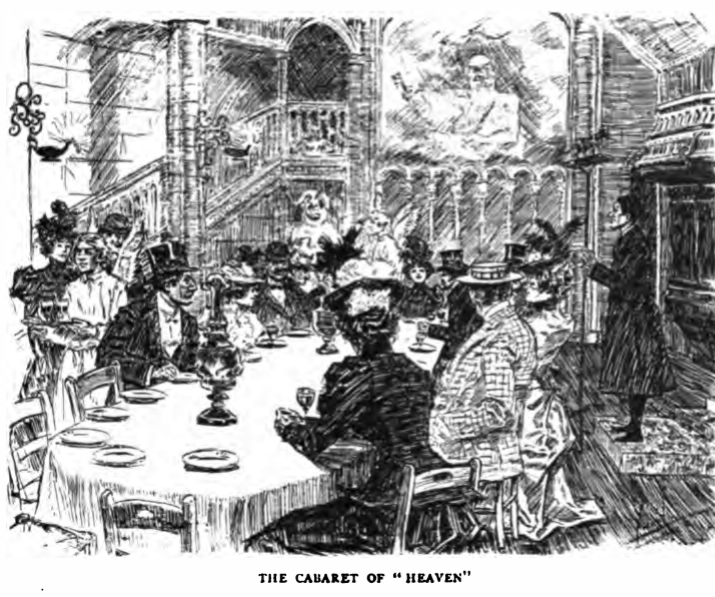

The souls that graced the vibrant Cabaret du Ciel were enveloped in a cold blue light. The patrons stepped into an ethereal realm featuring plays that depicted the bliss of heavenly afterlife. Divine, dreamlike harp music as well as gloomier organ music filled the air. A priest recited a typical invocation from a small altar. St. Peter would stick his head through a hole in the celestial cupola to sprinkle holy water from the heavens, while reenactments of scenes from Dante’s Paradiso mesmerised the audience. Waiters were adorned with lacy translucent wings and halos that seemed to glow in the ethereal light. Fluttering among sacred palms and gilded candelabras, the performers were dressed as nuns, angels, and saints. After a brief procession, guests were invited to a separate room in order to become angels themselves through an uplifting, ritualistic, choreographed performance involving singing, incense, getting dressed in white robes, being adorned with wings and halos, holding a harp, and gaining access to the empyrean – a cloud structure.

Many visitors, including British poet Arthur Symons, described the Cabaret du Ciel as a Parisian gem of divine enchantment, a slice of heaven, appreciating its serene atmosphere, uplifting show, and otherworldliness. However, some naysayers seemed to be of the opinion that it was strangely irreverent, vaguely sinister, or, worse – kitsch. Others said it was actually more depressing and grotesque than the Cabaret of Hell, which provided an intriguing spectacle.

Despite being staged like a religious ceremony, according to British visitor Trevor Greenwood, the Cabaret du Ciel had something dark and sinister in its ambiance and mise-en-scene. In his view:

“I just couldn’t believe my own eyes. What a room! Down the centre, lengthwise, was a long table covered with a white cloth… and lots of ash-trays: around the long table were seats, some already occupied by bewildered looking Americans: I suppose there would be about thirty seats all told. At the far end of the room was a small screen about eight feet square… presumably hiding a stage of some sort… And the room itself!! It might have been a temple for the sinister performances of black magic or something. The walls were covered with cheap imitations of religious knick-knacks. There was a large bell suspended from an imitation beam… and it was a wooden bell! Close to the bell was a banner-pole, with a silver coloured effigy of a bull mounted on top… The whole place reeked of something sinister… and the general effect was the very essence of tawdriness.”

An iconic and inspiring piece of the cultural landscape of 19th and 20th century Montmartre, the Cabarets of the Beyond provided a tantalising glimpse into vivid worlds lying beyond the veil by inducing uncanny, surreal Dantesque experiences. Testaments to the alchemical and polarising effects of art, the well-known entertainment venues were places where the ordinary was endowed with uncanniness, and where curious souls could immerse themselves in a sea of unfamiliar and strangely familiar sensations. Through their macabre and celestial decorations, their unsettling performances and music, as well as the otherworldly themes that they brought to life, the Cabarets created a space where the boundaries of reality and imagination were stretched and distorted.

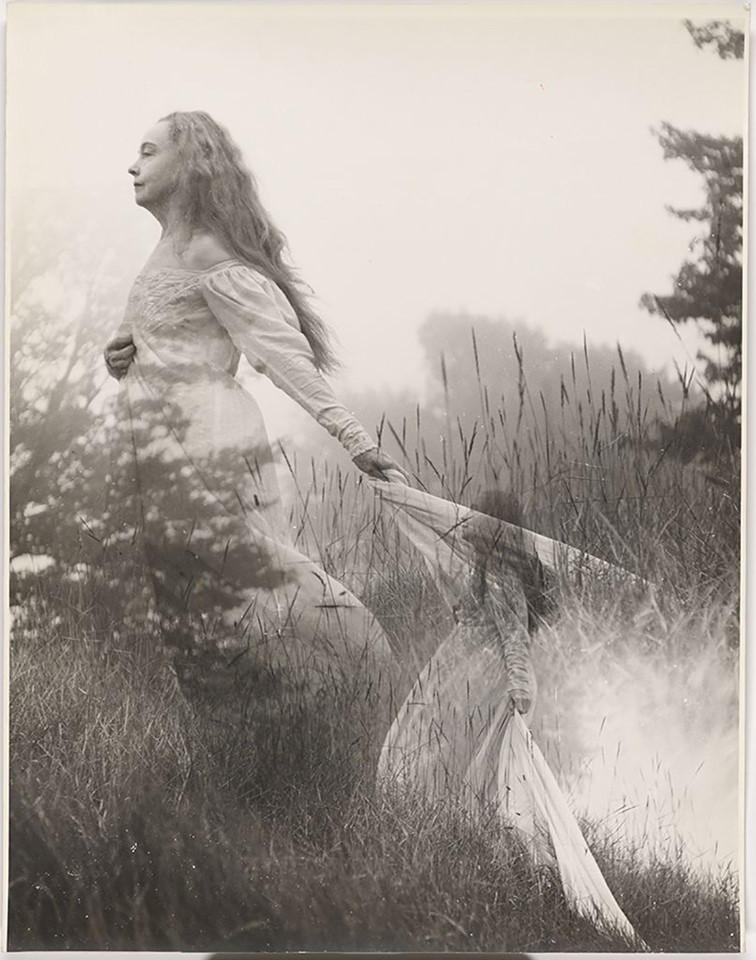

Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) is a memorable, experimental, surreal short film directed and written by Maya Deren. Referred to as poetic psychodrama, the film was ahead of its time with its focus on depicting fragments of the unconscious mind, externalising disjointed mental processes, dreams, and potential drama through poetic cinematic re-enactments brought to life by uncanny doppelganger figures. The enigmatic protagonist, played by Deren herself, enters a dream world in which she finds herself returning to the same spots and actions in and around her house, chasing a strange mirror-faced figure in a nightmarish, entangling, spiralling narrative. Whilst she ritualistically goes through nearly identical motions, with some slight changes, within a domestic space that is imbued with dread and a sense of doom, unreality, and foreignness – we also witness glimpses of multiple versions of herself, watching herself. The camera shifts from subjective to objective angles as the self-representation of the protagonist alternates between the dichotomous concepts of the self and the “other”. The domestic space revolves around certain recurrent symbolic objects. The film conjures up the uncanniness of dissociation or, more specifically, depersonalisation; self-obsession, a woman’s dual inner/outer life and subjective experience of the world, all congruous with Deren’s interest in self-transformation, interior states, surpassing the confines of personality and self-construct, as well as the self-transcending rituals of Haitian Vodou. The dream story, culminating in death, symbolically alludes to the -sometimes strange and terrifying- initial, non-rational stage of the Jungian process of the “transcendent function” (the symbolic confrontation with the unconscious) leading to the separation of awareness from unconscious thought patterns and the liberating reconciliation between the two opposites: ego and the unconscious, which also has the effect of integrating neurotic dissociations.

Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) is a memorable, experimental, surreal short film directed and written by Maya Deren. Referred to as poetic psychodrama, the film was ahead of its time with its focus on depicting fragments of the unconscious mind, externalising disjointed mental processes, dreams, and potential drama through poetic cinematic re-enactments brought to life by uncanny doppelganger figures. The enigmatic protagonist, played by Deren herself, enters a dream world in which she finds herself returning to the same spots and actions in and around her house, chasing a strange mirror-faced figure in a nightmarish, entangling, spiralling narrative. Whilst she ritualistically goes through nearly identical motions, with some slight changes, within a domestic space that is imbued with dread and a sense of doom, unreality, and foreignness – we also witness glimpses of multiple versions of herself, watching herself. The camera shifts from subjective to objective angles as the self-representation of the protagonist alternates between the dichotomous concepts of the self and the “other”. The domestic space revolves around certain recurrent symbolic objects. The film conjures up the uncanniness of dissociation or, more specifically, depersonalisation; self-obsession, a woman’s dual inner/outer life and subjective experience of the world, all congruous with Deren’s interest in self-transformation, interior states, surpassing the confines of personality and self-construct, as well as the self-transcending rituals of Haitian Vodou. The dream story, culminating in death, symbolically alludes to the -sometimes strange and terrifying- initial, non-rational stage of the Jungian process of the “transcendent function” (the symbolic confrontation with the unconscious) leading to the separation of awareness from unconscious thought patterns and the liberating reconciliation between the two opposites: ego and the unconscious, which also has the effect of integrating neurotic dissociations. distorted reflection in the polished knife, the camera follows her fluid bending movements as she is crawling on the staircase, whilst being strangely blown away by the wind in various directions within a claustrophobic space, levitating, trying to hang onto things, and eventually hanging in a crucified position against the wall. With her bat-like presence casting a larger-than-life shadow behind her, she gazes at her sleeping body on the couch through a point-of-view shot from the ceiling. This moment vividly evokes the concept of an out-of-body experience. She then watches a previous version of herself through the window, following the flower-holding, black cloaked figure outside. Unable to catch up, she enters the house, and the subjective camera movement switches to this version of her, whilst she catches a glimpse of the funereally dark, cloaked apparition walking up the stairs.

distorted reflection in the polished knife, the camera follows her fluid bending movements as she is crawling on the staircase, whilst being strangely blown away by the wind in various directions within a claustrophobic space, levitating, trying to hang onto things, and eventually hanging in a crucified position against the wall. With her bat-like presence casting a larger-than-life shadow behind her, she gazes at her sleeping body on the couch through a point-of-view shot from the ceiling. This moment vividly evokes the concept of an out-of-body experience. She then watches a previous version of herself through the window, following the flower-holding, black cloaked figure outside. Unable to catch up, she enters the house, and the subjective camera movement switches to this version of her, whilst she catches a glimpse of the funereally dark, cloaked apparition walking up the stairs. The elusive mirror-faced character is compelling and symbolically evocative. Nun, Grim Reaper, or mourner? The hooded black cloak and the ritual of bringing a flower to someone’s bed are immediately reminiscent of death, of mourning, and associations between bed/tomb and sleep/death. As the face of the obscure ghost-like manifestation is actually a mirror showing the reflection of the watcher, the scenario conjures up the idea of mourning one’s own death. After leaving the flower on the bed, the character disappears and the image of the woman also disappears and re-materialises several times, back and forth on the staircase. She then heads towards her own sleeping body whilst holding a knife, proceeding to try to stab herself before she awakens and sees a man holding a flower in front of her.

The elusive mirror-faced character is compelling and symbolically evocative. Nun, Grim Reaper, or mourner? The hooded black cloak and the ritual of bringing a flower to someone’s bed are immediately reminiscent of death, of mourning, and associations between bed/tomb and sleep/death. As the face of the obscure ghost-like manifestation is actually a mirror showing the reflection of the watcher, the scenario conjures up the idea of mourning one’s own death. After leaving the flower on the bed, the character disappears and the image of the woman also disappears and re-materialises several times, back and forth on the staircase. She then heads towards her own sleeping body whilst holding a knife, proceeding to try to stab herself before she awakens and sees a man holding a flower in front of her. The flower, a symbol of femininity, is therefore connected with death and sexuality, respectively. After a shot of the reflection of the man in the mirror next to the bed, we watch her lying down through the male gaze. The camera switches to the predatory look on his face, and, as he is about to touch her, she grabs the knife and tries to stab his face. At this point, the knife breaks a mirror instead, and the face of the man disintegrates into shards (another connection between the man and the dream figure), revealing an image -perhaps a memory- of waves and the beach. The man comes inside the house again to find the dead body of the woman on the couch- she committed suicide by cutting herself with a mirror.

The flower, a symbol of femininity, is therefore connected with death and sexuality, respectively. After a shot of the reflection of the man in the mirror next to the bed, we watch her lying down through the male gaze. The camera switches to the predatory look on his face, and, as he is about to touch her, she grabs the knife and tries to stab his face. At this point, the knife breaks a mirror instead, and the face of the man disintegrates into shards (another connection between the man and the dream figure), revealing an image -perhaps a memory- of waves and the beach. The man comes inside the house again to find the dead body of the woman on the couch- she committed suicide by cutting herself with a mirror. The multiplying of the character is connected to dissociation, alienation, emotional fragmentation, and potentially reintegration towards the end. The multiple incarnations of the woman evoke an internal schizoid narrative breathing life into alternative versions of herself- challenging her self-construct. Some of her personas are passively observing her more powerful, key-holding, knife-wielding persona. The suicide is symbolic, despite the fact that, in the final scene, it appears as if the layers of the dream world are peeled off and we have access to the real world. I believe the death symbolism is derived from Jungian psychology- i.e. the death and resurrection of consciousness. In light of this thought, the film can represent a visual representation of Jung’s Transcendent Function. What unfolds on screen is the process through which a person gains awareness of and confronts unconscious material driving their life in order to unite and re-channel the opposing energies of the ego and the unconscious into a third state of being, of wholeness. This would also have an integral effect that will merge the embodiments of the character’s dissociations. According to Jung, the process involves a challenging, unnerving unleashing of fantasies, dreams, and instincts. The sense of dread and panic evoked by the film matches this idea. The process is also associated with the notion of ego death in Eastern philosophies.

The multiplying of the character is connected to dissociation, alienation, emotional fragmentation, and potentially reintegration towards the end. The multiple incarnations of the woman evoke an internal schizoid narrative breathing life into alternative versions of herself- challenging her self-construct. Some of her personas are passively observing her more powerful, key-holding, knife-wielding persona. The suicide is symbolic, despite the fact that, in the final scene, it appears as if the layers of the dream world are peeled off and we have access to the real world. I believe the death symbolism is derived from Jungian psychology- i.e. the death and resurrection of consciousness. In light of this thought, the film can represent a visual representation of Jung’s Transcendent Function. What unfolds on screen is the process through which a person gains awareness of and confronts unconscious material driving their life in order to unite and re-channel the opposing energies of the ego and the unconscious into a third state of being, of wholeness. This would also have an integral effect that will merge the embodiments of the character’s dissociations. According to Jung, the process involves a challenging, unnerving unleashing of fantasies, dreams, and instincts. The sense of dread and panic evoked by the film matches this idea. The process is also associated with the notion of ego death in Eastern philosophies.