Altered Carbon is the only TV series that I know of that primarily and extensively deals with the transhumanist narrative of digitising, storing, and transferring human consciousness as a way of achieving immortality – and it’s a pretty gripping story if you have a little patience in the beginning whilst the universe is being fleshed out, in order to truly get immersed into the plot and connect with the characters. The story raises questions on human nature, identity loss in a changing, posthuman world, depersonalisation, and the necropolitical implications of a transhumanist future reliant upon biotechnology. The show is based on the eponymous cyberpunk novel by Richard K. Morgan, to which I will also refer to for further contextual information about the conceptual universe portrayed.

According to one of its founding fathers, Nick Bostrom, transhumanism is defined as “the intellectual and cultural movement that affirms the possibility and desirability of fundamentally improving the human condition through applied reason, especially by developing and making widely available technologies to eliminate aging and to greatly enhance human intellectual, physical, and psychological capacities”. At the same time, it’s also “The study of the ramifications, promises, and potential dangers of technologies that will enable us to overcome fundamental human limitations, and the related study of the ethical matters involved in developing and using such technologies.”

Bostrom adds: “Transhumanists hold that we should seek to develop and make available human enhancement options in the same way and for the same reasons that we try to develop and make available options for therapeutic medical treatments: in order to protect and expand life, health, cognition, emotional well-being, and other states or attributes that individuals may desire in order to improve their lives.”

The foundation of transhumanist beliefs and endeavours is built upon the principles of individual autonomy in selecting methods to enhance the body and mind, as well as ethical responsibilities when it comes to optimising living conditions and capabilities. Despite acknowledging potential health risks associated with such technologies, John Harris, bioethicist, advocates for scientific and technological advancements as a means to create a better society, and emphasises the importance of individuals taking responsibility for their actions.

Enhancement is thus a central belief of transhumanism, which seeks to advance humanity beyond its current natural state. There are many arguments pro and against the transhumanist movement. It has received criticism from opponents who are referred to as “bioconservatives,” including Francis Fukuyama who labelled transhumanism as “the most dangerous idea in the world.” The critiques revolve around the potential for misusing enhancement techniques, which has led to questions about the future of humanity and the accessibility and ethical considerations of these advancements. The opposing arguments state that transhumanist ideas pose dangers in terms of social-political and metaphysical implications. The social-political concerns revolve around the uncertainty of the equal distribution of radical technologies, while the metaphysical dangers involve the impact of these technologies on human identity and meaning. Both types of danger share a common fear, that transhumanism will lead to the end of humanity as we currently know it. As a result, people wonder if a science fiction-like future is possible or desirable, utopian or dystopian, and if we will evolve into something problematically different. Some bioethicists consider that our society is already incapable of morally monitoring its technological progress. There are also worries regarding the abuse of power and discrimination within this scenario. At the same time, our civilization has already made significant progress, but it still struggles to fully embrace or comprehend its own progress. If preceded by an enhancement in morals, transhumanist advancements are generally desirable, as people have always had an interest in improvement, from aesthetic to cognitive and biological. Genetic engineering would be taking such incentives many steps further, however, thus the concept is met with reasonable hesitation and polarising views. Is it against human nature or in alignment with its characteristic of seeking self-improvement?

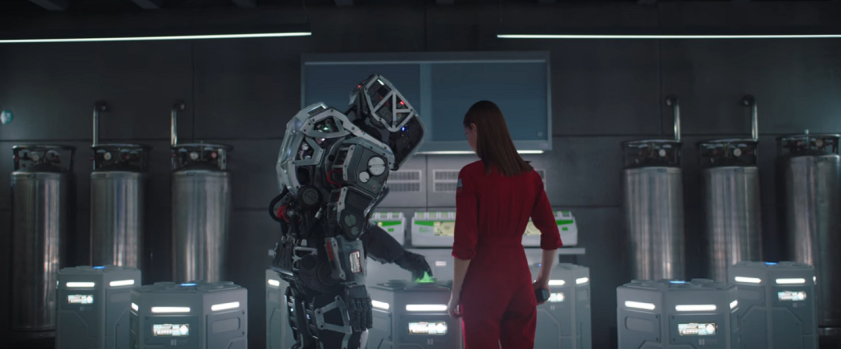

The concept of transhumanism has been intertwined with the science fiction genre since its inception. William Gibson’s novel Neuromancer (1984), a foundational text within the cyberpunk genre, features the character of Molly, a skilled assassin whose body has been technologically enhanced for increased efficiency and durability. Molly’s enhancements include surgically inserted glasses that seal her eye sockets and retractable scalpel blades beneath her nails. Apart from the belief that the human body can be enhanced and strengthened, transhumanism notably explores the potential of preserving consciousness and transferring it to a new body when the original body deteriorates due to age, illness, or weakness. According to Max More, a philosopher and futurist, despite diverging in opinions regarding other aspects, all transhumanists are in agreement that it is advantageous and achievable to utilise technology to overcome the biological limitations of death and aging. The pursuit of infinite life and youth is essential to the transhumanist mission, as the possibilities afforded by psychological, cognitive, and other enhancements will be constrained by a body that inevitably deteriorates and perishes. The dedication to hyperlongevity constitutes the central theme in the futuristic universe of Altered Carbon, where it’s called ‘Stack technology’, whilst ‘re-sleeving’ is the process through which consciousness is transferred from one body to another through the Stack devices (Bodies being referred to as ‘Sleeves’ throughout the book and the show).

In Altered Carbon, people are able to transcend and enhance their human physicality due to technology that not only stores their consciousness but can even be instantly transferred to bodies in faraway places i.e. other planets. For most citizens, human consciousness is recorded via the cortical stack which is implanted at the base of the skull when they are one year old. When someone dies, if they can afford it and if they haven’t been charged with serious crimes, they can have their stack uploaded, or ‘re-sleeved’ into other bodies; otherwise, their stack gets shelved. Death with no chance of resurrection is only guaranteed by irreversibly damaging the stack. That is, unless they can afford to have a D.H.F backup, which is a perfect duplicate of a person’s mind that gets regularly updated through a process known as ‘Needlecasting’ and can be stored in a safe place. Placing a duplicate consciousness in another body, known as ‘Double sleeving’ is also possible, but illegal and can lead to a death condemnation. Some people have ‘religious coding’ on their stacks, which theoretically means they cannot be revived, but this can be and is often bypassed by their relatives.

According to the film’s lore, the cortical stacks were made of alien metal and developed by technologically advanced creatures from another planet, who were also capable of manipulating human consciousness. The initial purpose of the devices was interstellar travel: human consciousness was downloaded and transmitted to Sleeves from distant planets through ‘Needlecasting’. After the non-terrestrial civilisation left Earth, human scientists reverse-engineered and refined the technology and created a system that allowed (some) people to constantly upgrade between bodies to preserve youth and health. Since this constitutes a regulated technology, there is a predictable ethical concern as wealthy citizens tend to be able to possess multiple bodies, travel across planets, and have a real-time copy of their consciousness stored in a safe place, whilst the poor might either get stuck in unhealthy, old, deteriorating bodies or live a fleeting existence.

An interesting aspect to note is that the book that the TV show is based on presents a wider variety of options that people have after death when it comes to re-sleeving, based on their budgets, such as clone replacements (the most expensive option), organic bodies, synthetic bodies, or the cheapest option, which is existing as a disembodied presence in a virtual reality setting. This summons up further questions about identity and reasons for existential crisis; for instance, the book characters who transfer their consciousness into synthetic bodies feel detached from their humanity, as they are no longer constrained by the limitations of human biology and they become increasingly removed from the physical sensations and emotions of their organic counterparts. Even more so, the ones who end up existing in digital form feel isolated, cut off from the real world, and deprived of sensory experience, although their disembodied cybernetic existence also has the advantage of not being limited by the constraints of physical bodies and the physical world. Their existence is, however, dependent on corporations and their host servers.

Continue reading

Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) is a memorable, experimental, surreal short film directed and written by Maya Deren. Referred to as poetic psychodrama, the film was ahead of its time with its focus on depicting fragments of the unconscious mind, externalising disjointed mental processes, dreams, and potential drama through poetic cinematic re-enactments brought to life by uncanny doppelganger figures. The enigmatic protagonist, played by Deren herself, enters a dream world in which she finds herself returning to the same spots and actions in and around her house, chasing a strange mirror-faced figure in a nightmarish, entangling, spiralling narrative. Whilst she ritualistically goes through nearly identical motions, with some slight changes, within a domestic space that is imbued with dread and a sense of doom, unreality, and foreignness – we also witness glimpses of multiple versions of herself, watching herself. The camera shifts from subjective to objective angles as the self-representation of the protagonist alternates between the dichotomous concepts of the self and the “other”. The domestic space revolves around certain recurrent symbolic objects. The film conjures up the uncanniness of dissociation or, more specifically, depersonalisation; self-obsession, a woman’s dual inner/outer life and subjective experience of the world, all congruous with Deren’s interest in self-transformation, interior states, surpassing the confines of personality and self-construct, as well as the self-transcending rituals of Haitian Vodou. The dream story, culminating in death, symbolically alludes to the -sometimes strange and terrifying- initial, non-rational stage of the Jungian process of the “transcendent function” (the symbolic confrontation with the unconscious) leading to the separation of awareness from unconscious thought patterns and the liberating reconciliation between the two opposites: ego and the unconscious, which also has the effect of integrating neurotic dissociations.

Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) is a memorable, experimental, surreal short film directed and written by Maya Deren. Referred to as poetic psychodrama, the film was ahead of its time with its focus on depicting fragments of the unconscious mind, externalising disjointed mental processes, dreams, and potential drama through poetic cinematic re-enactments brought to life by uncanny doppelganger figures. The enigmatic protagonist, played by Deren herself, enters a dream world in which she finds herself returning to the same spots and actions in and around her house, chasing a strange mirror-faced figure in a nightmarish, entangling, spiralling narrative. Whilst she ritualistically goes through nearly identical motions, with some slight changes, within a domestic space that is imbued with dread and a sense of doom, unreality, and foreignness – we also witness glimpses of multiple versions of herself, watching herself. The camera shifts from subjective to objective angles as the self-representation of the protagonist alternates between the dichotomous concepts of the self and the “other”. The domestic space revolves around certain recurrent symbolic objects. The film conjures up the uncanniness of dissociation or, more specifically, depersonalisation; self-obsession, a woman’s dual inner/outer life and subjective experience of the world, all congruous with Deren’s interest in self-transformation, interior states, surpassing the confines of personality and self-construct, as well as the self-transcending rituals of Haitian Vodou. The dream story, culminating in death, symbolically alludes to the -sometimes strange and terrifying- initial, non-rational stage of the Jungian process of the “transcendent function” (the symbolic confrontation with the unconscious) leading to the separation of awareness from unconscious thought patterns and the liberating reconciliation between the two opposites: ego and the unconscious, which also has the effect of integrating neurotic dissociations. distorted reflection in the polished knife, the camera follows her fluid bending movements as she is crawling on the staircase, whilst being strangely blown away by the wind in various directions within a claustrophobic space, levitating, trying to hang onto things, and eventually hanging in a crucified position against the wall. With her bat-like presence casting a larger-than-life shadow behind her, she gazes at her sleeping body on the couch through a point-of-view shot from the ceiling. This moment vividly evokes the concept of an out-of-body experience. She then watches a previous version of herself through the window, following the flower-holding, black cloaked figure outside. Unable to catch up, she enters the house, and the subjective camera movement switches to this version of her, whilst she catches a glimpse of the funereally dark, cloaked apparition walking up the stairs.

distorted reflection in the polished knife, the camera follows her fluid bending movements as she is crawling on the staircase, whilst being strangely blown away by the wind in various directions within a claustrophobic space, levitating, trying to hang onto things, and eventually hanging in a crucified position against the wall. With her bat-like presence casting a larger-than-life shadow behind her, she gazes at her sleeping body on the couch through a point-of-view shot from the ceiling. This moment vividly evokes the concept of an out-of-body experience. She then watches a previous version of herself through the window, following the flower-holding, black cloaked figure outside. Unable to catch up, she enters the house, and the subjective camera movement switches to this version of her, whilst she catches a glimpse of the funereally dark, cloaked apparition walking up the stairs. The elusive mirror-faced character is compelling and symbolically evocative. Nun, Grim Reaper, or mourner? The hooded black cloak and the ritual of bringing a flower to someone’s bed are immediately reminiscent of death, of mourning, and associations between bed/tomb and sleep/death. As the face of the obscure ghost-like manifestation is actually a mirror showing the reflection of the watcher, the scenario conjures up the idea of mourning one’s own death. After leaving the flower on the bed, the character disappears and the image of the woman also disappears and re-materialises several times, back and forth on the staircase. She then heads towards her own sleeping body whilst holding a knife, proceeding to try to stab herself before she awakens and sees a man holding a flower in front of her.

The elusive mirror-faced character is compelling and symbolically evocative. Nun, Grim Reaper, or mourner? The hooded black cloak and the ritual of bringing a flower to someone’s bed are immediately reminiscent of death, of mourning, and associations between bed/tomb and sleep/death. As the face of the obscure ghost-like manifestation is actually a mirror showing the reflection of the watcher, the scenario conjures up the idea of mourning one’s own death. After leaving the flower on the bed, the character disappears and the image of the woman also disappears and re-materialises several times, back and forth on the staircase. She then heads towards her own sleeping body whilst holding a knife, proceeding to try to stab herself before she awakens and sees a man holding a flower in front of her. The flower, a symbol of femininity, is therefore connected with death and sexuality, respectively. After a shot of the reflection of the man in the mirror next to the bed, we watch her lying down through the male gaze. The camera switches to the predatory look on his face, and, as he is about to touch her, she grabs the knife and tries to stab his face. At this point, the knife breaks a mirror instead, and the face of the man disintegrates into shards (another connection between the man and the dream figure), revealing an image -perhaps a memory- of waves and the beach. The man comes inside the house again to find the dead body of the woman on the couch- she committed suicide by cutting herself with a mirror.

The flower, a symbol of femininity, is therefore connected with death and sexuality, respectively. After a shot of the reflection of the man in the mirror next to the bed, we watch her lying down through the male gaze. The camera switches to the predatory look on his face, and, as he is about to touch her, she grabs the knife and tries to stab his face. At this point, the knife breaks a mirror instead, and the face of the man disintegrates into shards (another connection between the man and the dream figure), revealing an image -perhaps a memory- of waves and the beach. The man comes inside the house again to find the dead body of the woman on the couch- she committed suicide by cutting herself with a mirror. The multiplying of the character is connected to dissociation, alienation, emotional fragmentation, and potentially reintegration towards the end. The multiple incarnations of the woman evoke an internal schizoid narrative breathing life into alternative versions of herself- challenging her self-construct. Some of her personas are passively observing her more powerful, key-holding, knife-wielding persona. The suicide is symbolic, despite the fact that, in the final scene, it appears as if the layers of the dream world are peeled off and we have access to the real world. I believe the death symbolism is derived from Jungian psychology- i.e. the death and resurrection of consciousness. In light of this thought, the film can represent a visual representation of Jung’s Transcendent Function. What unfolds on screen is the process through which a person gains awareness of and confronts unconscious material driving their life in order to unite and re-channel the opposing energies of the ego and the unconscious into a third state of being, of wholeness. This would also have an integral effect that will merge the embodiments of the character’s dissociations. According to Jung, the process involves a challenging, unnerving unleashing of fantasies, dreams, and instincts. The sense of dread and panic evoked by the film matches this idea. The process is also associated with the notion of ego death in Eastern philosophies.

The multiplying of the character is connected to dissociation, alienation, emotional fragmentation, and potentially reintegration towards the end. The multiple incarnations of the woman evoke an internal schizoid narrative breathing life into alternative versions of herself- challenging her self-construct. Some of her personas are passively observing her more powerful, key-holding, knife-wielding persona. The suicide is symbolic, despite the fact that, in the final scene, it appears as if the layers of the dream world are peeled off and we have access to the real world. I believe the death symbolism is derived from Jungian psychology- i.e. the death and resurrection of consciousness. In light of this thought, the film can represent a visual representation of Jung’s Transcendent Function. What unfolds on screen is the process through which a person gains awareness of and confronts unconscious material driving their life in order to unite and re-channel the opposing energies of the ego and the unconscious into a third state of being, of wholeness. This would also have an integral effect that will merge the embodiments of the character’s dissociations. According to Jung, the process involves a challenging, unnerving unleashing of fantasies, dreams, and instincts. The sense of dread and panic evoked by the film matches this idea. The process is also associated with the notion of ego death in Eastern philosophies.